An Immortal Storm: The Inevitable Lifestyle of Detroit Teens

Detroit’s teens have evolved in the past 30 years, but so has Detroit. The question is, has It left a positive or negative impact for the teens?

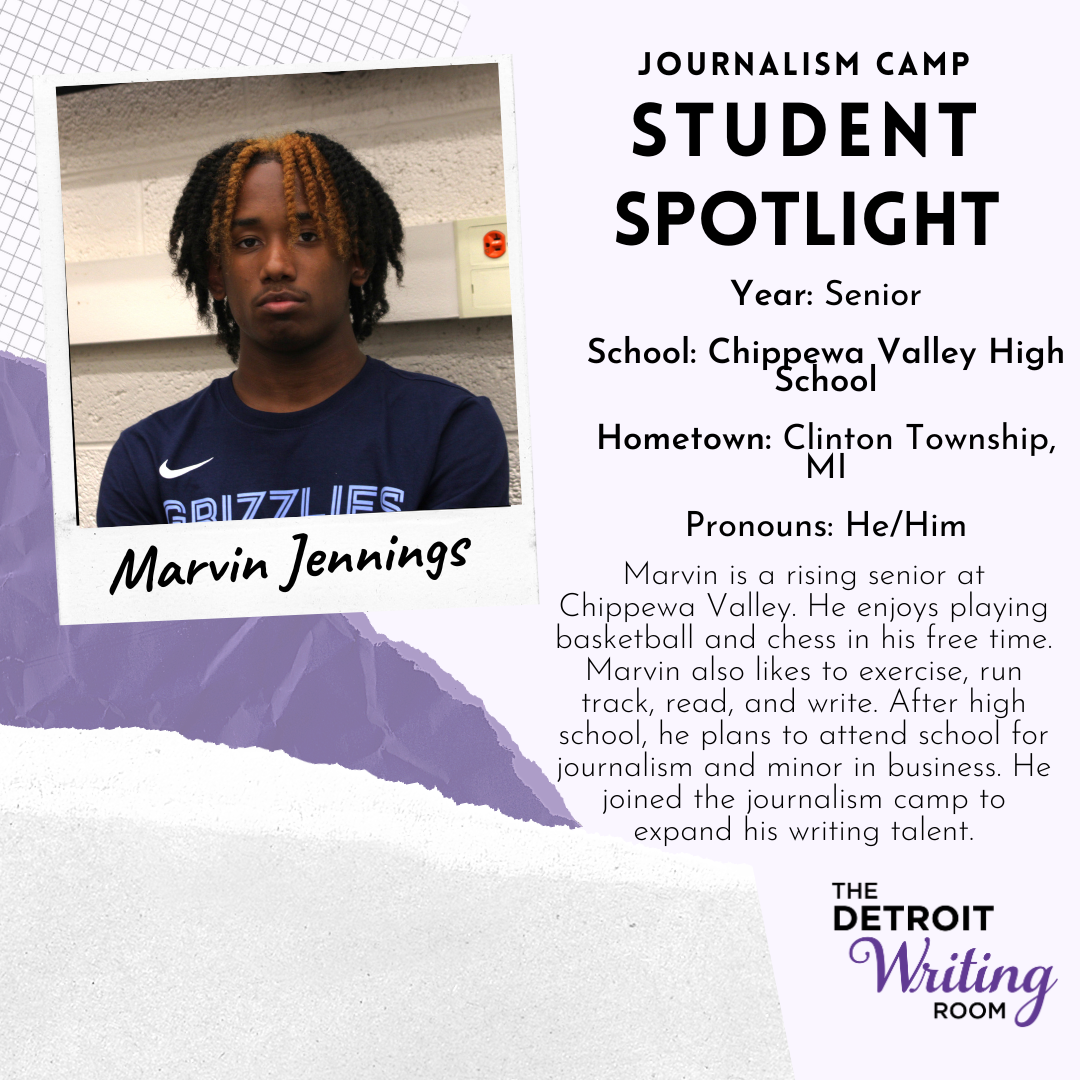

By Marvin Jennings Jr.

After 17 years of growing up in Detroit, Aniyah Hinds feels like she’s wasted her teenage years because she’s been so concerned about her safety.

“It sucks living in Detroit sometimes because there are privileges that get taken away from me that a normal teenager, or a teenager 30 years ago, would easily be able to do,” Aniyah says. “I can’t even walk my dog in the evening because it’s not safe. I want to be by myself, and just go out more and hangout with my friends, but I feel like this city is just an obstacle.”

Graduation photos of Detroiter Pamela Worthy.

Pamela Worthy, an adult who was a teenager back in the 70s, remembers being a 17-year-old in Detroit and had a different perspective on the city. Safety wasn’t as much of a concern.

“I grew up on Maplelawn off Wyoming. It was a predominantly mixed neighborhood. Blacks and whites lived there, and everyone looked out for each other. It was a nice area. It was just a lot of young people in the struggle loving each other and getting along with each other,” Worthy says.

These perspectives are important because they show that even though they lived in the same city, a lot can happen in the span of 30 to 40 years.

There’s always been a disconnect between teens and adults. When you think of a teen today, you might think, “They’re always on their phone, they’re lazy or they always stay in the house.” Do you ever sit and think why? The judgement is not fair to the teenagers who are going through something.

It's even harder on teens that don’t live in a safe part of Detroit. Teenagers realize how much crime happens in Detroit based off the news. This makes teenagers not want to go out even more, because it’s not guaranteed that they will come back home.

There is a 1 in 43 chance of becoming a victim of a violent crime and a 1 in 28 chance of becoming a victim of a property crime in Detroit, according to NeighborhoodScout, a database that gathers crime data. More than 99% of U.S. communities have a lower crime rate than Detroit, where the crime rate is 59%, NeighborhoodScout reports.

Due to these statistics, teens that live in Detroit are at risk.

Kaila Pickett, an 18-year-old, discussed how living in the city has impacted her mentality. She says she felt stripped of her teenage life due to incidents in Detroit.

“One of the obstacles I consistently faced living in Detroit was being scared that someone would break in your house in the middle of the night,” Kaila says. “I couldn’t tell the difference between fireworks and gunshots. It was New Year’s Eve, and I woke up thinking I heard fireworks, but they were gunshots. I just remember trembling in fear. I ran to my mom’s room, and she put on my favorite TV show. Ever since that day, I have never been home on New Year’s Eve.”

Kaila’s teenage life was tarnished just off one night. She didn’t feel safe, but there was nothing she could do until she could move out. Leaving gave her motivation, but at the end of the day, she asked herself, “Why do I have to go through this?”

Aniyah says the COVID-19 pandemic impacted her life living in Detroit, and she wanted her community to take the virus seriously. Aniyah has lived in Detroit since she was born. She doesn’t live in the most dangerous part of Detroit, but she says you can never be too cautious.

“I’ve already been accustomed to staying in the house,” she says. “Covid just makes everything worse. I’m literally trapped in this house because if I go out then I will get infected. It feels like a movie, or like an apocalypse. People in Detroit don’t listen. The news says to wear masks, and they don’t. They say stay inside, and they don’t. All they’re doing is spreading the virus, and it’s not helping our community.”

Aniyah has already made up her mind that her teenage years have been wasted simply by living in Detroit. This leads to her staying in the house and staying on her electronics — the only thing she can use to get in touch with her friends without going out.

Worthy, who is now in her 60s, explains Detroit used to be a better environment. If you go by the places she used to hang out at, they’re “decayed,” she says.

“When you look at the neighborhood I lived in now, it’s ran down and decayed,” she says. “It’s totally different. It’s as if it was never built, or like a storm went through it. Over time people just abandoned places that were hot back in the day. All that’s left is the memories.”

Downtown Detroit in August 2023. Photos by Keturah West

Some parts of Detroit are going through gentrification, but there were still about 22,000 vacant homes in the city, The Detroit News reported in 2020. The city has lost a majority of its population since its peak in the 1950s.

According to Worthy, Detroit was better when she was a teen. There weren’t as many abandoned homes and places, and people treated each other better.

“When I was a teenager you did more listening — you didn’t open your mouth. We were nice to elderly people, and we looked out for them,” Worthy says. “People are more about themselves instead of helping each other. That’s what I see in a lot of teens today.”

Adults feel a sense of pity for their teenage kids because most, if not all, parents want their kids to do what they did and more. Part of that is having a good time in the city.

Adults talk about how much fun they had in the city when they were teenagers, and you can’t help but wonder why and how Detroit got so bad to the point where this next generation can’t enjoy the city as much as their parents.

Or their parents are overprotective because of what they see and hear on the news. Every time they look at the news — whether it’s about a school shooting, sex trafficking or even a kidnapping, adults tend to think of their own children. But Detroit hasn’t always been a city where you couldn’t go out at night because you might hear shooting or arguing.

The lifestyle of this generation is also different because of the prevalence of electronic devices. Compared to teenagers 30 years ago, teens handle situations differently. Instead of meeting up with our friends consistently, we can just call or text them.

A 2018 survey of 13 to 17 year olds by the nonprofit Common Sense Media found 95% have a mobile device. Electronics keep teens from going out as much, and it also keeps them in the house more than they should be.

So not only are teens in the house using electronics daily, but they barely go outside because of the potential threats in the city. It’s a lose-lose scenario, but would you rather be unhealthy and sit in the house, or risk your safety?

Overall, if you look at the teen and adult perspectives in Detroit and how they grew up, you can see that the energy shifted in a different direction. We as people should make Detroit a better place not just for teenagers, but for everyone to enjoy the city that it used to be.